When Ideas Terrify Even Their Creators

Innovation is meant to be glorious—cue applause! Maybe even a standing ovation and a TED Talk. But history has a dodgy sense of humour: the brightest ideas often leave their creators whispering in the dark, “What have I done?”

Mary Shelley nailed this back in 1818. In Frankenstein, a young genius electrifies a corpse and—ta-da!—creates a monster. No champagne, no applause, just horror. It’s the original startup nightmare: (MVP) minimum viable product plus (MR) maximum regret.

A century later, scientists split the atom. Discovery! Nobels! And then mushroom clouds. Robert Oppenheimer, the mastermind steering the work in the New Mexico desert, didn’t boast. Instead, he muttered the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Not a line you print on the recruitment posters.

And that pattern hasn’t slowed down. In fact, the shadow side of innovation feels more alive than ever. Take Elon Musk, who co-founded OpenAI to advance AI safety, then became one of the technology’s most vocal critics:

“If AI has a goal and humanity just happens to be in the way,” he warned, “it will destroy humanity as a matter of course without even thinking about it… It’s just like, if we’re building a road and an anthill happens to be in the way.” That’s not hype. That’s Silicon Valley channelling Shelley.

Pressed on just how bad it could get, Musk didn’t soften: “There is some chance, above zero, that AI will kill us all. I think it’s slow, but there’s some chance.” Later, he even slapped on numbers: “I think there’s some chance that it will end humanity. I probably agree with Geoff Hinton that it’s about 10% or 20%.” When your estimate of human extinction is a coin toss away from winning a pub quiz, you know something’s up.

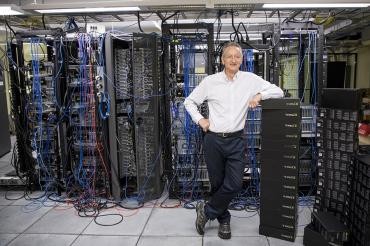

Meanwhile, Geoffrey Hinton (right), the so-called “Godfather of AI,” walked out of Google in 2023 because his own invention spooked him.

His confession? “My fear isn’t that AI becomes conscious—it’s that it becomes competent.” In other words, it won’t need to feel like us to outdo us. Asked on the TV show 60 Minutes whether humanity knows what it’s doing, he said:

“No. I think we’re moving into a period when, for the first time, we may have things more intelligent than us.” Not exactly the sort of line you drop into a retirement speech.

And it isn’t just AI. Jennifer Doudna, (left) co-inventor of CRISPR gene editing, admitted to nightmares in which someone asked her to “design” a child with glowing blue eyes. The power to edit the human genome came with visions of a genetic arms race she never intended to start.

Facebook started as “connect your campus”; it ultimately turbocharged misinformation and undermined elections worldwide. The Internet was meant to make knowledge more accessible. It also unleashed a tsunami of misinformation, giving conspiracy theories a global reach.

Alfred Nobel invented dynamite to help miners, not generals. He was so horrified when his invention fueled warfare that he rewrote his legacy entirely, funding the Nobel Prizes to promote peace and progress.

THE PATTERN BEHIND THE HORROR

Behind the horror lies a stark truth. It’s not that ideas are evil. It’s that they tend to outgrow our ethics.

Once unleashed, ideas evolve in directions their creators never anticipated. The more we are promised progress, the darker the shadow and the brighter the light, the darker that shadow gets.

So what defines a true visionary? It’s not just the ability to predict the future, or to imagine new worlds. What distinguishes those with vision is a willingness to confront their worst possible nightmares and to know where they stand.

Mary Shelley and eighteen understood that perfectly. Her story wasn’t anti-science; it was anti-hubris. It warned that creators must take responsibility for their creations, whether flesh, atom, or algorithm.