So you want to be famous!

There’s a play waiting to be written in which the Devil appears and offers a writer or an artist huge and permanent fame. The only drawback, says the devil, is that “it won’t happen in your lifetime!”

We’re so accustomed to hearing about successful people that we’re sometimes blind to what it takes to succeed. We celebrate success, but often forget how much failure came first. Some of history’s greatest minds stumbled, were ignored, or ridiculed—yet their legacies endure.

For some, the devil’s bargain is the other way around. “I’ll make you famous, but you’ll soon be forgotten.”

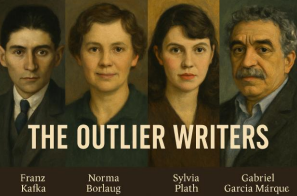

Take Norman Ernest Borlaug, for example. What, you’ve never

heard of him, despite his Nobel Prize in 1970? Not quite singlehandedly, he revolutionized agricultural production, known as the Green Revolution. Borlaug won multiple honor’s for his work, apart from the Nobel Peace Prize, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal. The near-invisible Borlaug today was one of only seven people to have received all three awards.

An article in The Atlantic (1997) titled “Forgotten Benefactor of Humanity” describes Borlaug as someone who “has saved literally millions of lives, yet he is hardly a household name.” Public awareness remains low enough to merit that phrasing, decades after his significant achievements, Yet, outside of the agricultural, development, and scientific communities, his name is seldom

invoked in mainstream media or popular culture. There are no big recent movies, massmarket biographies, or widely taught school modules that reach the public broadly. He is credited with saving over a billion people from starvation and is called the father of the Green Revolution. Yet he is less remembered than some now-famous artists who sold virtually nothing during their careers.

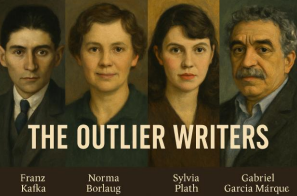

Let’s take a closer look at the invisibles, or Outliers, whom I am sometimes drawn to “meet” in my regular website columns at www.andrewsbooks.site.

PAINTERS

Let’s start with the struggling artists who never really made it in their lifetime. For example, Vincent van Gogh sold only one painting in his lifetime, the Red Vineyard. Think of that. Just one painting! Poor van Gogh, he was shy, withdrawn, and utterly unable to promote himself. As for having a marketing plan, forget it!

Paul Cézanne, too, was rejected by salons and derided by critics. Only much later, after death, was he hailed as the father of modern art. Georges Seurat fared little better; his lovely pointillist work was dismissed as eccentric and hard to sell.

Claude Monet struggled financially before the Impressionist movement gained popularity. It was almost too late, and he famously attempted suicide by drowning in the Seine.

Henri Rousseau was ridiculed as a “naïve” painter during his lifetime, experiencing no commercial success. What do you think he would have thought about the sale of his 1910 picture Les Flamant’s, which was bought at Christie’s in New York in May 2023 for, wait for it….$43.5 million? Similarly, Amedeo Modigliani was unable to sell his portraits during his lifetime. Yet somebody paid US $157.2 million for one of his paintings in May 2018.

As I’m not a painter, I admit to finding it hard to relate to some of these people, but it’s different when it comes to writers.

WRITERS

Herman Melville, of Moby Dick fame, found that his work was a commercial flop and died thinking himself a failed writer. Franz Kafka, too, published little and insisted his work be burned. Naturally, marketing was entirely alien to him.

Much the same could be said about Marcel Proust, who had to self-finance his first volume of In Search of Lost Time. He studiously avoided literary cliques, which of course put paid to any real marketing in those days.

John Keats, the poet, was savaged by critics; sold few books and died young, convinced he’d failed. Meanwhile, the famous Henry David Thoreau had little success in his lifetime, and Walt Whitman ended up self-publishing and selling copies of his much later, absolute bestseller, Leaves of Grass.

Sylvia Plath, now one of the most studied poets of the 20th century, had only modest recognition while alive. Her only published novel, The Bell Jar, was released under a pseudonym in Britain just weeks before she died in 1963, and her poetry collections sold few copies.

It was only after Plath’s death that her work was championed, winning the Pulitzer Prize posthumously in 1982 and cementing her as a cultural icon. Her story underlines how fame and influence can arrive too late for the artists themselves.

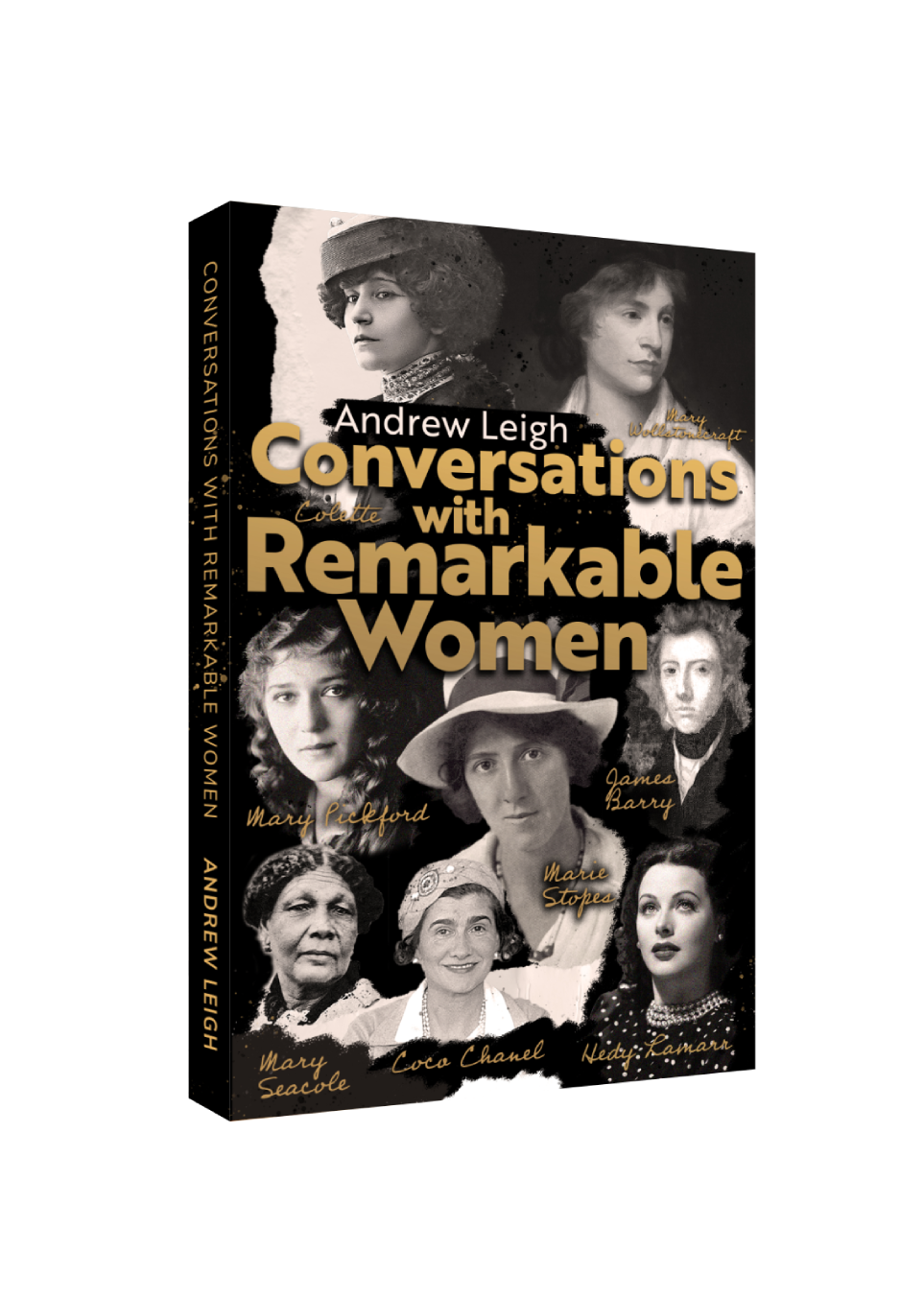

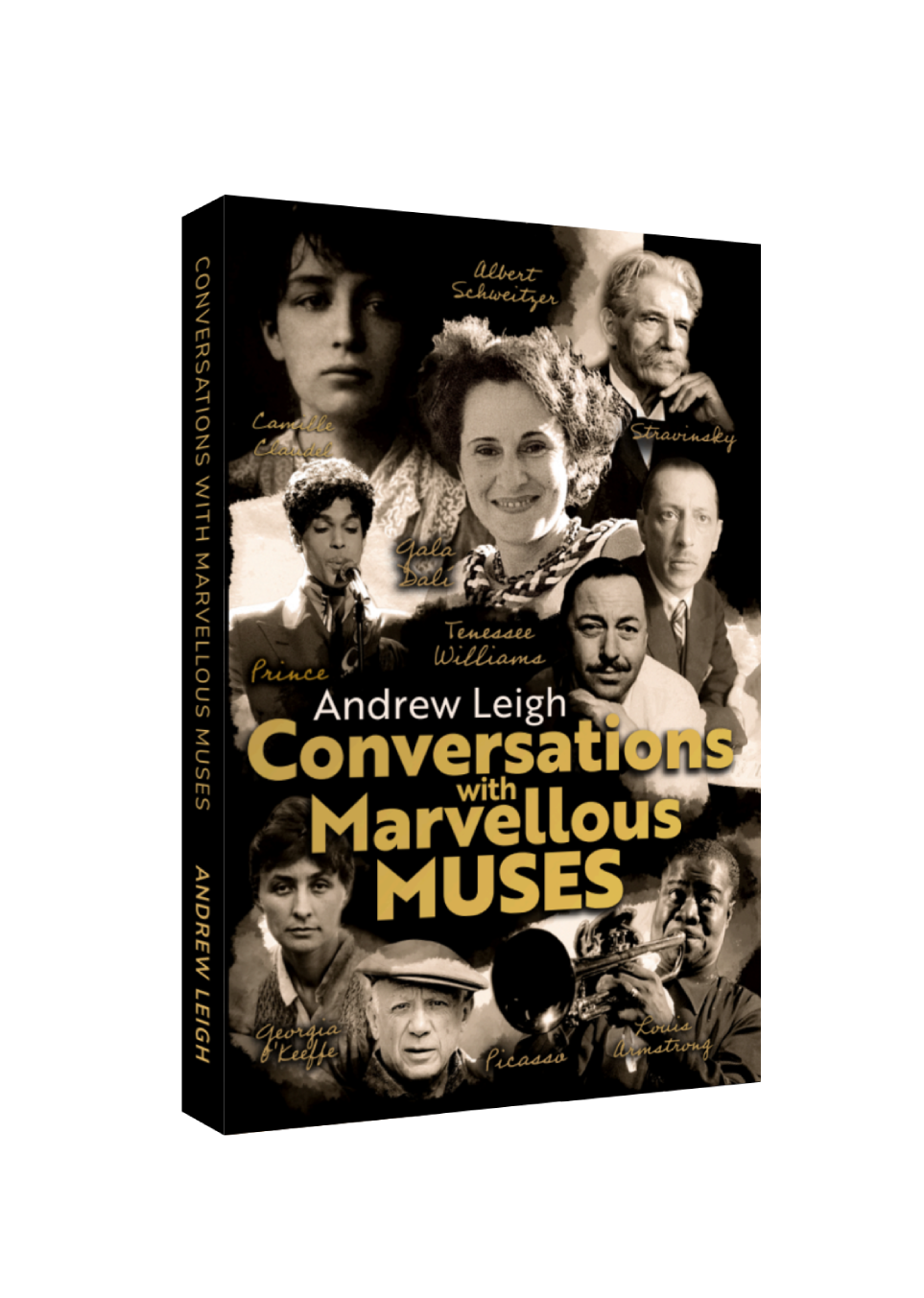

I don’t rank myself among any of the above, of course. But when I check on the sales of my two new books: Conversations with Remarkable Women, and Conversations with Marvellous Muses, I have to remind myself that things might yet be better!